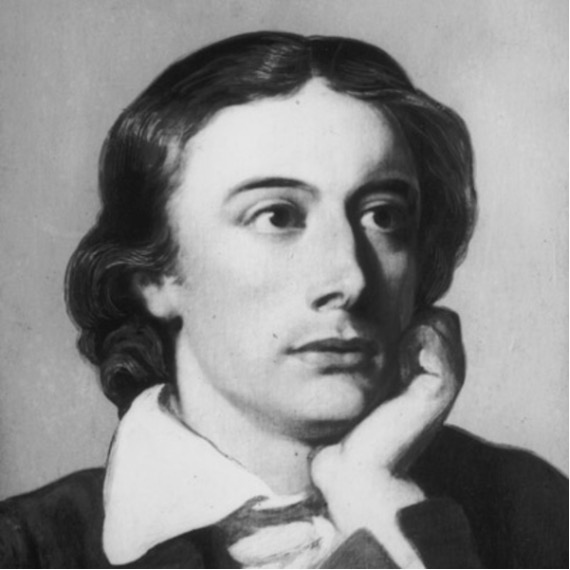

Introducing John Keats

John Keats was an English lyrical poet, prominent in the second generation of Romantic poets. He is known for his sensuous appeal and use of vivid imagery. Keats’s reputation grew only after his death at twenty-five years old. This collection includes his six most famous odes and four sonnets, including his most famous sonnet and three others dedicated to other poets that inspired Keats or had an influence on his own work. This collection aims to expand the accessibility of Keats’s work online, as well as extend the understanding of his imagery and philosophy. Applying scholarly research to Keats’s poems to analyze his influence on diction, versification, and style, this edition highlights the parts of his work that make Keats so significant. The goal of this collection and analysis is to expand Keats’s work and significance to (early) readers who do not read or have a knowledge base in English Romantic poetry.